What is waste worth by Renny Ramakers

What is waste worth?

Waste. What is the value of waste? In Cape Town everything is re-used and re-used and re-used until it falls apart. In Cape Town nothing is waste. Everywhere, from townships to more well–to-do areas, we can find products made of used or re-used materials. If it isn’t for economic necessity, it is for love of shabby chic.

This is how last week I started my keynote at Department of Design in Cape Town. Department of Design is a three weeks event, initiated by the Dutch consulate, with Christine de Baan as program director. What makes this official Dutch participation in Cape Town Design Capital 2014 so special, is that it is not a ‘business as usual’ presentation of design objects. But this initiative rather seeks collaboration with South Africa on topics such as energy, water, health, education and town planning. It is a program full of lectures and workshops featuring Ekim Tan (Play the City), Michelle Provoost (INTI), Jeroen Warmerdam (Tygron), Kristian Koreman (Zus) and others.

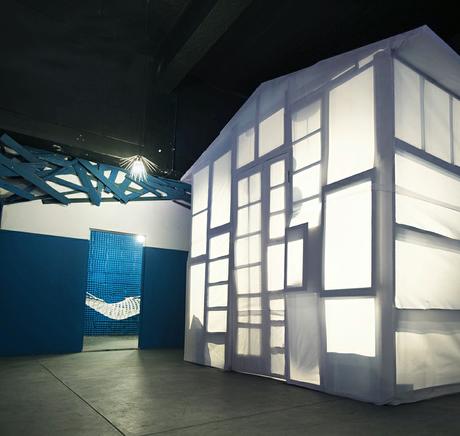

When we were asked to design an environment for this event, it was from the outset clear to me that this should be a welcoming landscape in which visitors could discuss, relax or have a coffee and that it should be entirely made of waste, sourced locally, executed by local producers and that after closure of the event all the materials should go back into the flow.

A beautiful little church in the township Khayelitsha, made of corrugated steel and painted in blue and white, was our guideline for the colours. It is our tribute to the anonymous people who created this.

In our Amsterdam based studio we searched the Internet and discovered numerous places where we could get waste. We made a plan and our team went to Cape Town to collect the materials, especially wooden planks, crates, corrugated steel and bicycles. It was a journey full of surprises.

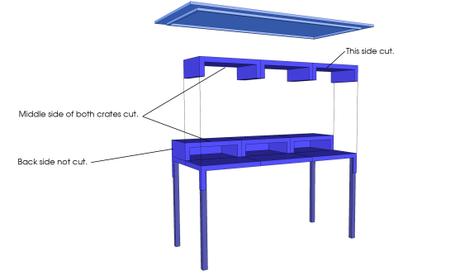

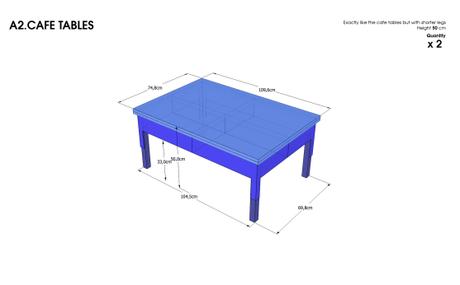

In Cape Town nothing is waste. Even more so, waste is scarce. There is too much need. Consequently we had to pay a lot more than we expected, even for almost rotten planks and window frames. We had to skip the idea of using used crates in our furniture pieces. They just were not available. So we decided to make an exception and bought them new. Another limitation was the use of corrugated steel to cover the walls of the auditorium. Our idea was to make a lot of incisions in this material to give it more character. But once in Cape Town, we soon discovered that this should not be done. Since this material proves to be so valuable for the communities. It provides a roof above their head. Therefore every cut in this material would be an irreparable waste.

The biggest challenge was to work from a distance. In our studio in Amsterdam we made renderings and technical drawings and we monitored the execution by the local producers. Eventually we managed to achieve a 90% result of our renderings while 10% was improvisation on the spot.

At first sight, I wished that some details would have been executed more precisely. But when everything was set up and the lights were on, the overall look and feel took this initial desire away . It was amazing to see how an environment covered with a seemingly random but consequent pattern of wooden planks full of cracks and splinters could give such a beautiful result. It was also an experience to see how everything fitted in this environment, the stools, the tables, the mobile coffee bar, the little houses… With a strong framework it does not matter whether there are a few planks more or less, and whether some details are not like they are supposed to be. It is a framework that allows improvisation.

Re-using materials and products is what we have done from the outset. Among the highlights of our first presentation in Milan in 1993 were Tejo Remy’ s Chest of Drawers and Rag chair. In 2010 we presented UP, a business model based on the redesign of dead stock. Re-using waste and leftovers represents the ultimate circular economy. But it is also a process with restrictions. It is not only that waste can be scarce, but it also fact that most companies prefer to destroy their leftovers instead of bringing them back into circulation.

Be that as it may, making things out of leftovers is a playful process with lots of opportunities for improvisation. It generates a unique sense of beauty, the beauty of imperfection, which is such a relief in our times of super perfection. Piet Hein Eek showed this already in 1991 with his scrap wood cabinet. Although we are used to design with leftovers, the Cape Town assignment was a surprisingly new experience with more roughness, and less control than we are used to. Improvisation on the spot had to bring everything together.

After closure of the event everything has to go back into the flow. My dream is that piles of blue wooden planks will be dropped in one of the townships, so that they can be used to make new houses and that at my next visit, I will find some totally blue houses or houses with just a few patches of blue. This would be the cherry on the cake.